Currently I am reading

The

Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art by

David Lewis-Williams.

What a fascinating book!!

As much as it is about the origins of art, it is also about the origins

of human consciousness. Some of the

themes of the book I find most interesting are his connecting normal, universal

neurological activity to our conceptions of reality. For example, many, many

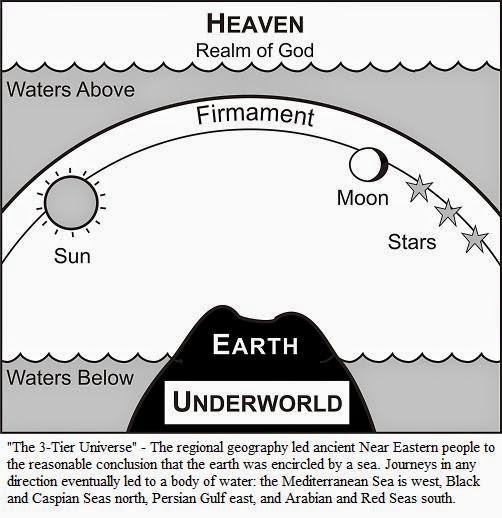

cultures conceive of a three-tiered cosmos; a “normal” level at which “normal”

life and perception take place, a lower level and an upper level (in our

culture that might be hell and heaven).

The author believes this conception arises from neurological activity

that affects our awareness in altered states, like dreaming and

hallucinating. They tend to take on

either the qualities of pressure and sinking feelings or soaring and flying

sensations. Hence, they are later explained

as an underworld and an overworld.

Another theory he develops is that mark making also follows

universal tendencies, those being grids, stars, zigzags etc.

These “images” are what we see when we close

our eyes and are called “phosphenes.”

(More on phosphenes

here).

As

he states on P. 127, “People in this condition are seeing the structure of

their own brains”. So, then when we make these marks, when we idly scratch away

at notepads, we are drawing our own brain.

Whoa! Pretty amazing.

|

| “Phosphenes”

28” x 24”, 2008 (yes, this is exactly what the inside of my brain looks like. That's the whole point, is it not?) |

But I am most interested in his theories on the origins of

image making (and, by extension, art).

What’s interesting? Well, one

thing he says is that it could not have arisen from body art. Wow, jewelers,

fashion designers, tattooists, scarification aficionados et al: you have just been demoted! Could this be the origin of Craft vs Art? There's a thought.

Lewis-Williams believes that 2-D representations, which he

calls “parietal” (stuff on walls) art

are a wholly different paradigm. He says that order to “invent pictures” (my quotes, not his) one needs a socially

agreed upon context, something that relies on language. He also notes that it’s a real chicken and

egg dilemma: what arose first? Our

ability to perceive images as meaningful or our ability to make them? He dispatches with some popular theories too:

that drawing arose from cavemen with charcoal embers scratching in the ground

out of boredom and happening to notice they look like something. Or that the shapes of rocks looked like

animals so they just kind of helped them along with pigment. No, these images rely on there being an

existing “database” for 2-D images having meaning.

OK, I am no anthropologist and I may wish I was a

neurologist, but, sadly, I am not one! How

frustrating as I wish I had enough knowledge to really discuss this. I still

find value in the theories he is disparaging.

What about all those facial recognition modules in the brain? What about how we see shapes in clouds? That is surely nature and not nurture (although I gather his point is that without

the social context of language, those images we see would remain “autistic” and

locked away in our individual experience and even un-remembered as we would not

have the language to codify them and to a great extent would be just more

useless detritus of being alive.)

He points out that there is no evidence of stages of

inventing drawing/image making. No evidence of

an “artist” trying out different subjects or styles.

And this really gets me! Why, oh

why, is there so very little images of humans and of human faces? What is with all the bison and aurochs?? I get

it, bison and aurochs were very important to them, but surely so were their own

faces and bodies. I am really astounded by the fact that we did not choose to

draw ourselves!!!

One thing the author doesn’t discuss (but I am not finished

yet, actually, so maybe he does in the last 80 pages) is how images making/drawing

develops in children. Children make

scribbles for a while, which seem to gradually coalesce into something more

meaningful. Then they go on a trajectory

of attempting “realism” and I think (but can’t say for sure since I am also not

a child development expert) that they compulsively draw human forms. Is that nurture? Could be.

But I think the draw (pun intended) towards figuration is very deeply

encoded into us…so why didn’t the cavemen do it??

|

| Representation of a human puking by me at age 3 or 4. |

Someone go do a Ph.D. thesis on this, please!

.jpg)